August 21, 2025

How to prevent muscle loss during weight loss

Losing weight can also mean losing muscle. Learn how strength training, protein, and daily movement can help you keep lean mass, protect metabolism, and feel stronger.

Written by

Head of Clinical Strategy, Sword Move

Muscle loss is the health risk no one talks about during weight loss

Weight loss programs often celebrate the number on the scale. But when that number drops without context, something important can get lost. That something is muscle.

While the goal may be to reduce fat, many weight loss strategies, especially those driven by medication or calorie restriction, also cause lean muscle loss. This outcome is a significant potential side effect of GLP-1 use and presents a long-term health risk.

The Sword Summary Warm-up

Don’t have time for the full workout? We’ve got you covered with a quick, high-intensity session. Here are the key takeaways:

- A calorie deficit can reduce fat and muscle, especially if weight loss is fast or movement drops.¹

- The most reliable muscle-protection combo is resistance training plus adequate protein, with a steady, sustainable pace of weight loss.¹,²

- If you need structure and accountability, Sword Move helps you build movement habits and retain strength with weekly plans, wearable insights, and one-on-one support from a Physical Health Specialist.³,⁴

Weight loss is not easy, but persistence is the key

If you are losing weight for health reasons, you’re already doing something hard and hopeful: changing direction. This article is here to help you protect the part of you that makes “results” feel good in real life, like climbing stairs without thinking, carrying groceries easily, getting up off the floor, and feeling steady on your feet.

That is muscle. And it deserves a plan.

Why muscle loss can happen during weight loss

Most weight loss strategies are built around one lever: creating a calorie deficit. That works for reducing body weight, but your body does not automatically know you only want to lose fat.

When energy intake drops, your body pulls from available stores. If your muscles are not being “asked” to stay (through strength training and regular use), the body can break down lean tissue alongside fat.¹ The risks associated with this muscle loss are serious.

The risks of GLP-1 muscle loss can rise when:

- Weight loss is rapid (bigger deficits are harder to sustain and can increase lean mass losses)¹

- You are not doing resistance training or your day-to-day movement drops¹

- Protein intake is not enough to support muscle protein synthesis, especially in older adults²

Muscle isn’t just about strength or appearance. It’s a critical part of your metabolic system, your functional ability, and your protection against injury. Losing it during weight loss can lead to fatigue, weakness, chronic pain, and mobility challenges, even if the pounds come off. And the risk isn’t theoretical. Clinical research shows that up to 39% of lean muscle mass is lost during GLP-1 medication usage¹. Muscle loss is linked to increased fatigue, a higher risk of falls, MSK conditions, and costly downstream care.

It also matters how you are losing weight. With GLP-1 medications, experts have raised concerns that a meaningful portion of weight lost can come from lean mass, particularly when people are inactive⁵.

Muscle is more than mass, it’s a long-term health asset

After understanding the risk, we need to reframe how we think about muscle. It isn’t just a side effect of weight training or a cosmetic bonus. Muscle plays a central role in health, especially during weight loss.

Muscle supports metabolism by helping the body burn calories at rest². It protects joints and bones by stabilizing movement and absorbing impact³. It reduces injury risk by improving balance and strength, and it enables everyday function like walking, lifting, and climbing stairs⁴.

When you lose lean muscle during weight loss, you don’t just get lighter, you get weaker. That weakness can set off a chain reaction: lower energy, less movement, more joint stress, and eventually, pain or injury. This is a compounding risk that leads to physical and financial consequences over time. Now that we’ve seen what muscle does for you, let’s break down what causes it to disappear during weight loss.

What causes muscle loss during weight loss?

Many of the most popular weight loss programs contain hidden risks. Calorie restriction or pharmacological appetite suppression may reduce fat, but they also reduce essential lean tissue if not properly supported¹. Muscle loss is most often triggered by¹:

- Rapid calorie restriction, which can cause the body to burn muscle for fuel

- Lack of physical activity, especially resistance-based movement

- Inactivity during weight loss, particularly in desk-based or sedentary lifestyles

- Prescription weight loss medications, including GLP-1s like semaglutide, that reduce appetite without supporting movement

Without intentional strength training or structured activity, the body can shed both fat and muscle when in calorie deficit. Most people don’t know this is happening because weight is the only number they’re tracking. Muscle needs to be actively preserved.

Who’s most at risk for muscle loss during weight loss?

Some people are more vulnerable than others. Whether due to age, medication, or lifestyle, certain populations lose muscle faster or more significantly during weight loss. Those most at risk include:

- Adults over 40, who naturally lose muscle mass with age (a condition known as sarcopenia)⁵

- People using GLP-1 medications without integrated movement programs¹

- Those with metabolic conditions like prediabetes, insulin resistance, or obesity

- Inactive individuals who sit for most of the day or avoid exercise

- People following aggressive weight loss plans that don’t include strength training

If you fall into one of these groups, structured movement should be part of any weight loss approach.

How to prevent muscle loss during weight loss

Preventing muscle loss takes intention. It won’t happen by accident, especially during a weight loss program. But the interventions are simple and proven to work. The pillars that work best together are resistance training, protein, and a pace you can sustain. Here’s a 5-step plan to help you maintain lean muscle while reducing fat:

1) Do resistance training at least twice a week

If you only pick one upgrade to your plan, pick strength work. This doesn't mean you need gym equipment, heavy weights, or high-intensity workouts. Evidence supports implementing resistance exercise during diet-related weight loss to reduce the risk of fat-free mass loss and improve strength outcomes.¹

Regular resistance training using bodyweight and bands is enough to help you retain muscle.The following are good options:

- Bodyweight strength (sit-to-stand, wall push-ups, step-ups)

- Resistance bands

- Dumbbells or kettlebells at home

- Short sessions that build consistency over intensity

If you are new to strength training, start lighter than you think you need. The goal in week one is repeatability.

2) Keep aerobic activity, but do not let it replace strength

Cardio supports heart health, mood, and energy. Public health guidelines recommend adults aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, plus muscle-strengthening activity on 2 or more days per week.⁶

For muscle protection, think of cardio as supportive. Strength is the anchor.

3) Prioritize protein, spread across the day

Adequate protein supports muscle protein synthesis, especially during a calorie deficit and with aging. Research also suggests that shifting more protein earlier in the day (not only at dinner) can improve the muscle-building signal after an overnight fast, although long-term body composition effects can vary by person.²

If you have kidney disease or other medical conditions, talk with your clinician or dietitian before increasing protein.

4) Avoid the “too steep” deficit

Fast weight loss can be motivating on the scale, but it can be punishing for muscle and adherence. A steadier pace gives your habits time to form and your body a better chance to preserve lean mass while you reduce fat.¹

5) Track the signals that matter, not only the scale

The scale cannot tell you what you lost.

Add 2 to 3 markers that reflect muscle preservation:

- Strength progress (more reps, heavier load, easier movement)

- Step count or active minutes

- Waist measurement or how clothes fit

- Energy, steadiness, and confidence with daily tasks

If those signals are improving, you are building a more sustainable base for lasting, healthy weight loss.

Prevent muscle loss with consistent movement that fits real life

A common reason muscle loss sneaks in is not lack of willpower. It is lack of structure.

People start a calorie deficit, feel more tired, move less without noticing, and skip strength sessions because they are unsure what to do or how to progress. Then the body adapts in a predictable way¹.

This is where support, personalization, and accountability can matter just as much as motivation.

Sword Move helps you retain strength while you lose weight

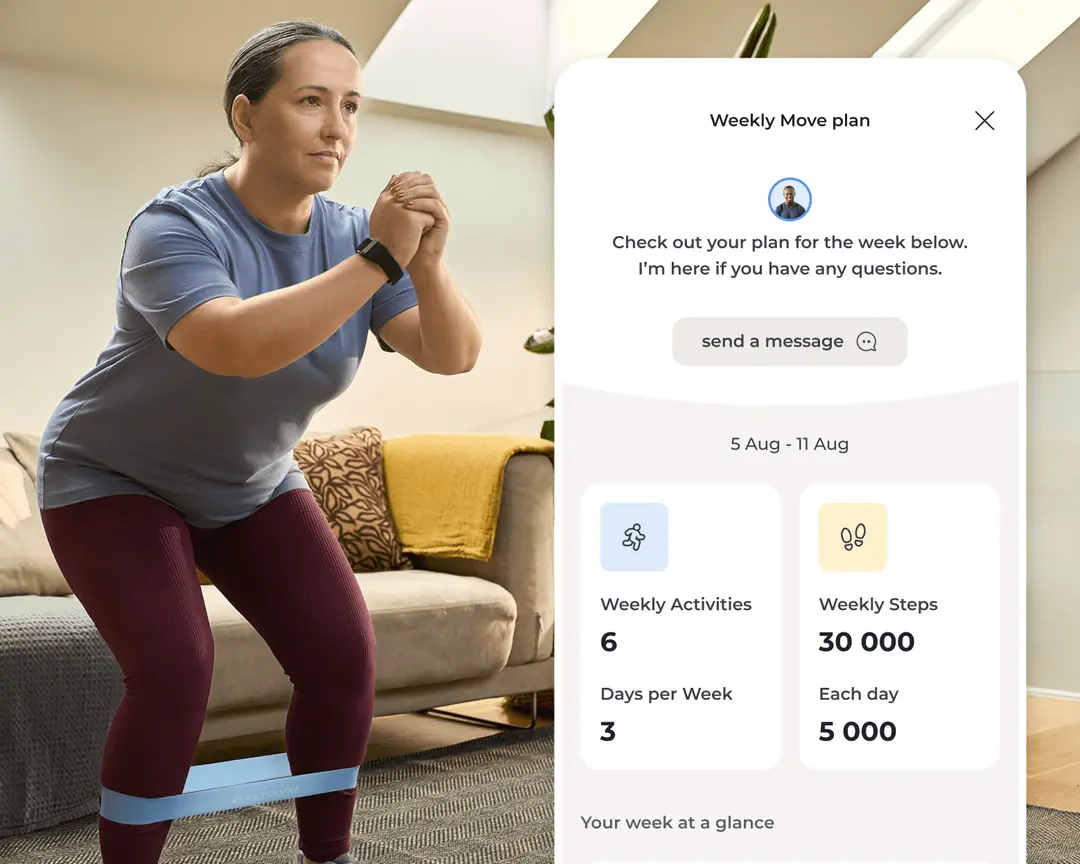

Most people do not need another generic “get fit” program. They need a plan that meets them where they are, removes guesswork, and makes movement feel doable on a Tuesday, not just aspirational on a Sunday.

Sword Move is a whole-body movement solution designed to address low pain, reduce risk of injury, and help members move more consistently, which helps avoid the costly consequences attributed to physical inactivity.

What it feels like to use Move

Move is built around three practical elements:

- A dedicated Physical Health Specialist: Each Move member is paired with a dedicated Physical Health Specialist who holds a Doctor of Physical Therapy degree, and they deliver weekly, tailored Move Plans that evolve as you do.

- A plan that reduces guesswork: Each week, you get a personalized plan with targeted movements and step goals based on your lifestyle, job function, progress, and schedule.

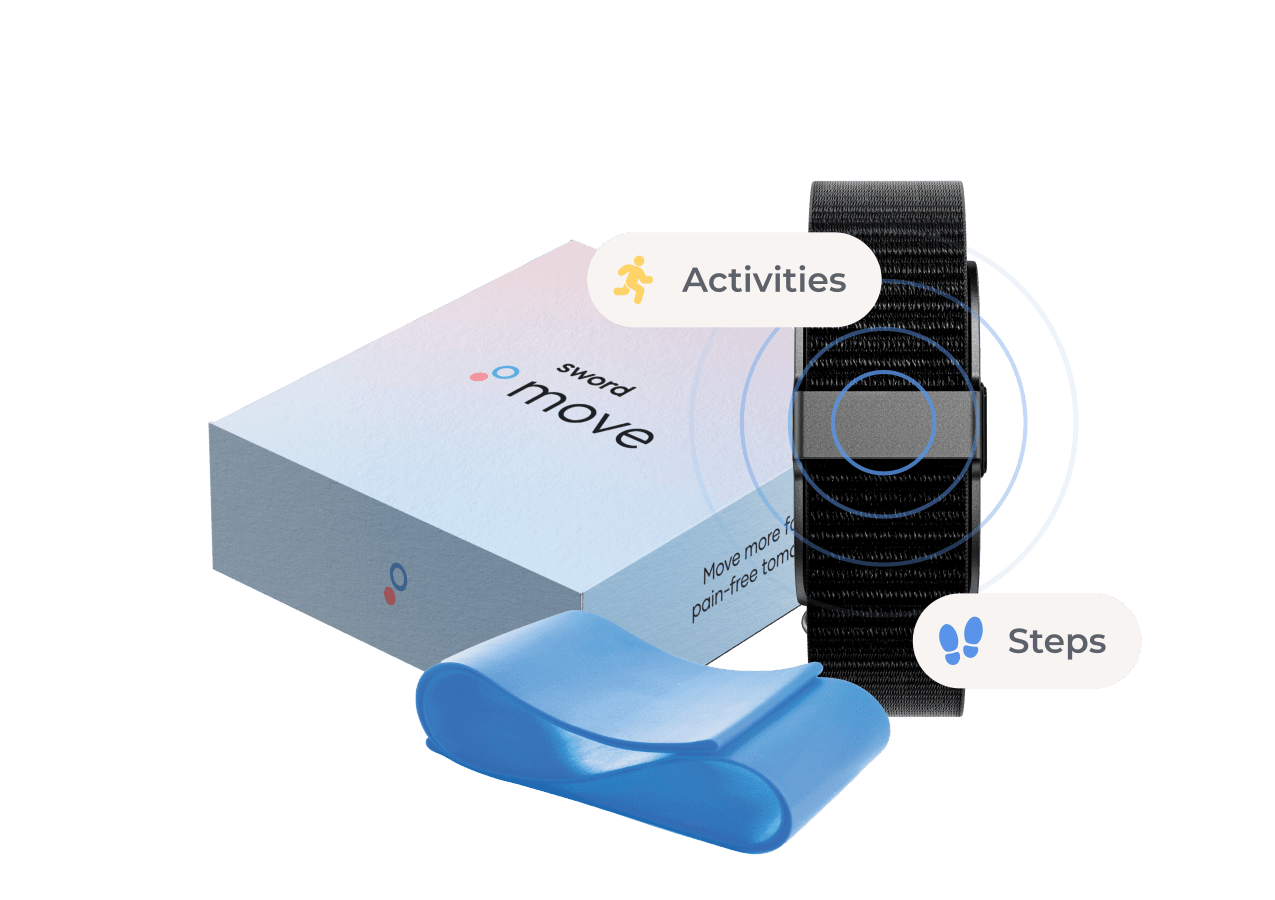

- AI guidance using the Move Wearable: Members can use a complimentary Move wearable or connect an Apple Watch or Fitbit to track steps, heart rate, and activity. That data helps inform ongoing plan adjustments to match your progress.

Weight loss is not only about “losing pounds.” You need to make sure you don't negatively impact your health or capacity. Move is designed to make strength and movement consistent enough that your body has a reason to keep muscle.

Get started with Sword Move for whole-body strength

1. Tell us about you

We’ll learn about your goals, job type, lifestyle, and movement history.

2. Match with a Physical Health Specialist

Your dedicated Sword Move specialist will create a personalized plan just for you.

3. Receive your Move kit

You’ll get a free Move wearable and resistance bands delivered to your door.

4. Start moving with your personalized plan

Pair your Move wearable and begin weekly goals built around your activity level, routines, and progress.

Right across all of Sword's member populations, the Move program consistently delivers measurable and impressive results:

- 69% of “inactive” and “insufficiently active” members reach “active” or “healthy active” status within 10 weeks¹²

- 4.5 movement sessions per week on average¹³

- Sedentary time reduced by 1 hour 22 minutes per day for previously “inactive” or “insufficiently active” members¹⁴

- 90% of members reported feeling moderately or much better¹⁵

These outcomes are not specific to weight loss medication use, but they align with what most weight loss plans struggle to deliver: consistent, progressive movement that people actually complete regularly. Sword Move supports muscle retention, drives behavioral change, and helps members build sustainable routines.

Lose weight, keep your strength, and stay active

The most frustrating weight loss stories are not the ones where the scale does not move. They are the ones where the scale moves, but life feels smaller. If you want results that lasts, protect the thing that makes you resilient: your muscle.

Here is the simplest overview of a safe and successful strategy:

- Create a moderate deficit, not an extreme one

- Try to strength train at least twice a week

- Eat enough protein to support your muscle

- Keep daily movement from quietly disappearing

- Track capability, not only weight loss

If you are trying to do all of that while juggling work, family, stress, pain, or medication side effects, you do not need more pressure. You need a plan that is realistic, and support that is consistent.

That is exactly the gap Sword Move is designed to close. It turns “I should move more” into weekly guidance, small wins, and steady progress you can feel.

Join 500,000+ people using Sword to end their pain

Recover from pain and get moving from the comfort of your home with clinically-proven expert care

Footnotes

Binmahfoz A, Dighriri A, Gray C, Gray SR. Effect of resistance exercise on body composition, muscle strength and cardiometabolic health during dietary weight loss in people living with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2025;11(3):e002363. University of Glasgow repository landing page (open access). https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/361857/

Deutz NEP, Wolfe RR, et al. Impacts of protein quantity and distribution on body composition. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2024. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1388986/full

Sword Health. Proactive AI Pain Care with Guided Movement (Sword Move). https://swordhealth.com/solutions/move

Sword Health. Get started with Sword Move to get stronger from home. https://swordhealth.com/articles/get-started-with-sword-move

Sanchis-Gomar F, Neeland IJ, Lavie CJ. Balancing weight and muscle loss in GLP1 receptor agonist therapy. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2025;21:584–585. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01160-6

World Health Organization (WHO). Physical activity (recommendations for adults, including muscle-strengthening 2+ days/week). https://www.who.int/initiatives/behealthy/physical-activity

Sousa AS et al. Impact of sarcopenia on fall risk: A clinical perspective. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN. 2022;50:63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.06.007

Sword Health. Move Program Design Specifications. 2024. Internal data.

Sword Health. MET-min analysis. 2024. Internal dataset.

Sword Health. Move Book of Business, H1 2024. Internal data.

Sword Health. Member reassessment data (5+ weeks). Internal data.

Sword Health. PGIC scores, Sword member base (2023–2024). Internal data.